Modern cars are increasingly equipped with large displays, touch interfaces, and digital controls—just like smartphones. Many celebrate this as progress. And anyone who voices criticism is quickly met with:

“It’s like the Blackberry—buttons are a thing of the past.”

Or even: “Ok, Boomer…”

But this comparison isn’t just a case of apples and oranges—it’s dangerously oversimplified. A car is not a smartphone. And road traffic isn’t social media scrolling.

Why the Blackberry Analogy Doesn’t Work

The shift from Blackberry-style physical keys to touchscreen smartphones was a logical step—in an environment designed for it:

- You actively look at the device

- The interaction is part of your attention

- Mistakes are usually harmless

In a car, however:

- Your eyes must stay on the road

- Controls need to be operable blindly and intuitively

- Mistakes can lead to serious accidents—or cost lives

So calling physical buttons “obsolete” doesn’t hold up in terms of safety. This isn’t about nostalgia—it’s about functionality in context.

Studies Show: Touchscreens Are Distracting

Many tests and studies have shown that touchscreens significantly increase driver distraction:

- ADAC (2022) found that simple tasks like adjusting the radio or climate control took 15 to 30 seconds in cars with touchscreen-only controls—equivalent to driving up to 800 meters without looking at the road at highway speed.

(Source: ADAC – Bedienung im Auto) - EuroNCAP plans to include display-related driver distraction in its future vehicle safety ratings.

- Research from Sweden (VTI) and the UK shows: Drivers who use touchscreen menus are distracted longer than those speaking on a hands-free call.

The more you scroll, tap, and search—the longer you’re distracted.

This Isn’t Just About “Old People”

A common stereotype is: “People who want buttons just aren’t tech-savvy.”

That’s simply not true. It’s not about digital literacy—it’s about safety, clarity, and reaction time. Cars are environments where intuitive operation can literally save lives—and that applies to all generations.

Why Our Senses Need Diversity—and So Do Cars

Humans are multisensory beings. When we drive, we use:

- Sight to monitor traffic

- Hearing to react to sounds and alerts

- Touch to feel and operate controls

Each sense has biological limitations in bandwidth and capacity. For example:

- Vision is powerful, but focused—only a small central area (fovea) provides high resolution.

- Peripheral vision is lower resolution and relies on interpretation.

The brain is not a passive receiver—it filters and prioritizes information:

- Selective attention filters out irrelevant input

- Multitasking limits prevent us from processing two visual tasks simultaneously

- Working memory is limited to about 4–7 elements

- Context awareness determines what gets priority

Overloading the visual channel is a safety risk. You cannot safely monitor traffic and navigate a touchscreen interface at the same time.

That’s why it’s smarter and safer to distribute information and controls across multiple senses, rather than focusing everything on visual input alone.

Multimodal Feedback Helps—Touch Alone Overwhelms

Touch interfaces demand constant visual confirmation: focus, find the right menu, touch the right spot. In contrast, auditory and haptic feedback reduce visual load and support faster, safer reactions.

Yes, touchscreens can vibrate or beep—but these features are often disabled by users (they’re “annoying”) and they still require visual confirmation. They add feedback, but don’t replace visual control.

Research confirms: Multimodal human-machine interfaces (HMIs) with combined visual, haptic, and audio feedback lead to:

- Faster reaction times

- Fewer user errors

- Greater objective and perceived safety

(Source: ResearchGate – Multimodal HMI for Highly Automated Vehicles)

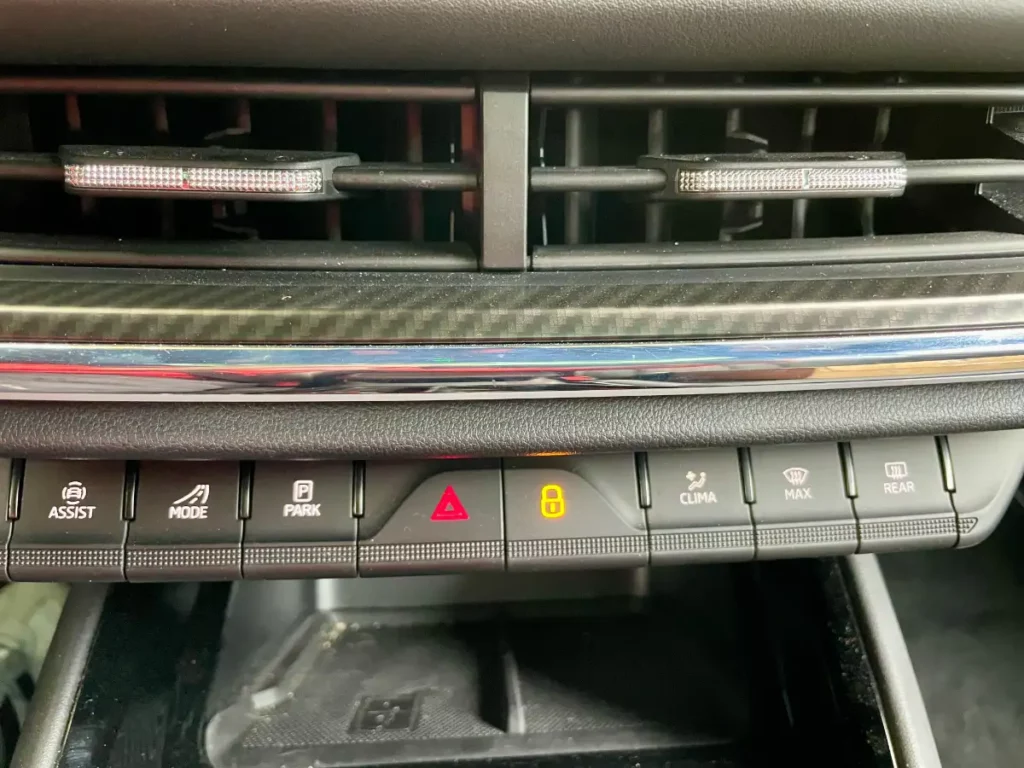

The Škoda Steering-Wheel Lever: A Practical Example

Škoda’s lever for ACC and Travel Assist demonstrates how well-designed tactile controls can outperform touchscreens:

- Adjust speed up/down

- Activate or deactivate the system

- Confirm or ignore detected speed limits

All with one hand—without looking, fully intuitive.

It works because:

- Each function has a distinct position or motion

- The system provides immediate visual or audio confirmation

- Your eyes stay on the road

This isn’t nostalgia—it’s multisensory ergonomics in action. Something many modern touch-only setups lack—including overloaded steering wheel controls with vague feedback.

Voice Control: Helpful, but Not a Replacement

Voice assistants (like Škoda’s “Laura”) are useful and have earned their place—for tasks like navigation or media control. When conditions are ideal, voice commands reduce the need to touch or look.

But in practice:

- They’re not always reliable (dialects, background noise, unclear phrasing)

- They require cognitive attention

- They’re not faster than a button

Example: “Laura, set temperature to 21 degrees” requires more time and mental effort—and may not work the first time. A knob does it in one second, without thinking or looking.

Bottom line: voice control is a supplement—not a substitute.

Conclusion: Buttons Aren’t Outdated—They’re Smart

In software design, the rule is: Don’t make me think.

In cars, it should be: Don’t make me look (away).

Vehicle cockpits aren’t places for design experiments or symbolic gestures. They are spaces that demand clear, safe, and functional ergonomics.

A button in the right place is not a step back. It’s a statement for safety.